| |

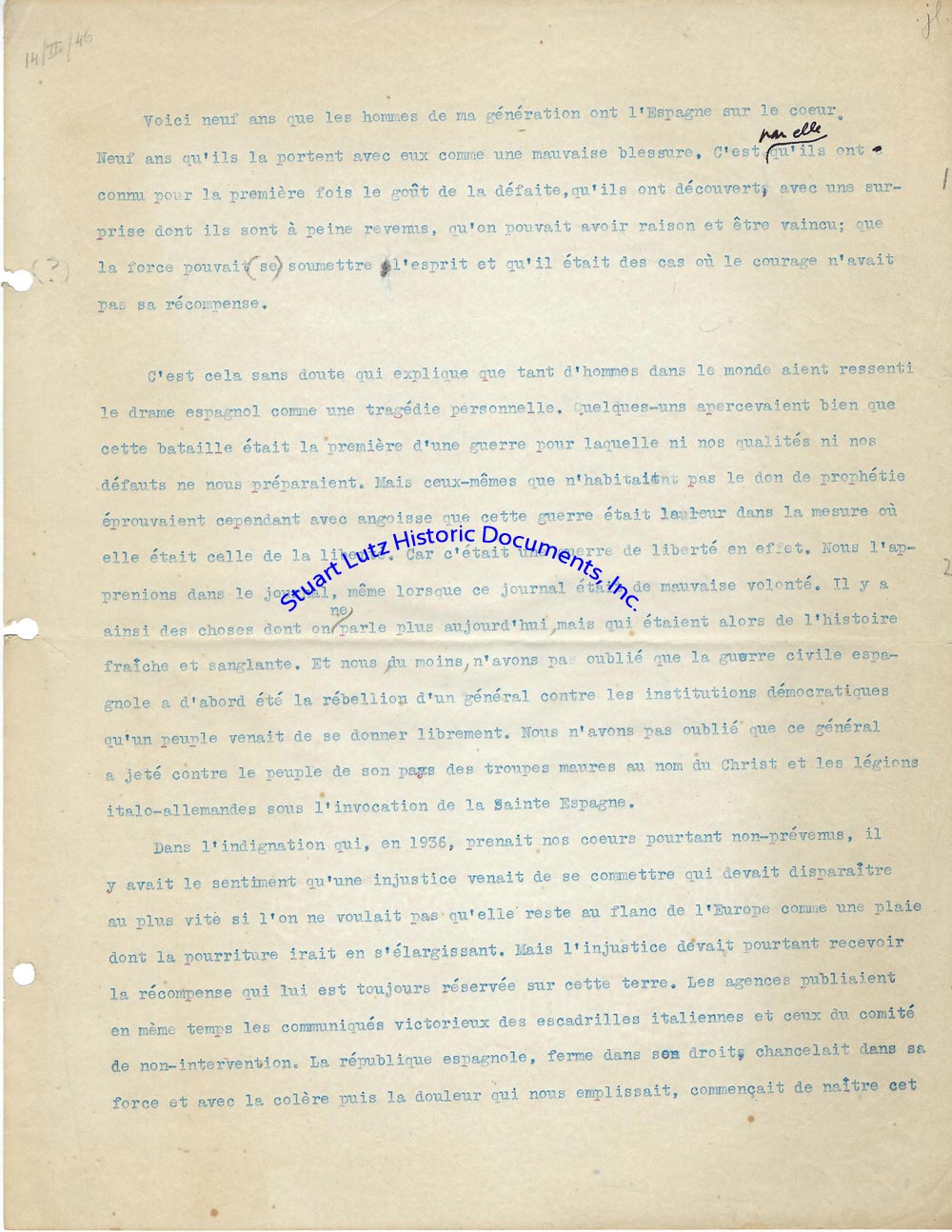

ALBERT CAMUS COMPARES THE SPANISH CIVIL TO WORLD WAR II IN A LENGTHY TYPESCRIPT OF HIS PREFACE TO THE BOOK L’ESPAGNE LIBRE; HE WRITES ONE OF HIS MOST FAMOUS AND REPRODUCED QUOTES: “IT HAS BEEN NINE YEARS NOW THAT THE MEN OF MY GENERATION HAVE CARRIED SPAIN IN THEIR THOUGHTS. NINE YEARS THAT THEY CARRY LIKE A SERIOUS WOUND. THAT EXPERIENCE HAS GIVEN THEM THEIR FIRST TASTE OF DEFEAT AND THE INSIGHT, REALLY A SURPRISE FROM WHICH THEY HAVE BARELY RECOVERED, THAT YOU COULD BE IN THE RIGHT AND YET BE BEATEN, THAT FORCE COULD SUPPRESS THE SPIRIT, AND THAT THERE WERE TIMES WHERE COURAGE WAS NOT REWARDED. NO DOUBT THAT EXPLAINS WHY TO SO MANY MEN ALL OVER THE WORLD, THE SPANISH DRAMA FELT LIKE A PERSONAL TRAGEDY…”

ALBERT CAMUS (1913-1960). Camus was a Nobel Prize-winning French author best known for his absurdism and works like The Stranger and The Plague.

TMS. 5pgs. 1945. N.p. A lengthy typescript, in French, by Albert Camus. It concerns the Spanish Civil War (1936 to 1939). This manuscript was Camus’s preface to the book L’Espagne Libre (Paris: Calman-Lévy, 1946). Writing just after World War II, in which he took an active role in the resistance against the Nazis, Camus muses back on the Spanish Civil War, often called a “dress rehearsal for World War II”. Camus felt personally connected to the Spanish Civil War, since his mother was Spanish. The English translation of his writing is as follows: “It has been nine years now that the men of my generation have carried Spain in their thoughts. Nine years that they carry like a serious wound. That experience has given them their first taste of defeat and the insight, really a surprise from which they have barely recovered, that you could be in the right and yet be beaten, that force could suppress the spirit, and that there were times where courage was not rewarded. No doubt that explains why to so many men all over the world, the Spanish drama felt like a personal tragedy, some realizing that this was the first battle in a war for which neither qualities nor flaws had prepared us. But those very same ones who did not don the mantle of prophecy came to feel with anguish that this war was theirs to the degree that it was a war of liberty. For it was in fact that, a war of liberty. We found out about it in the papers, even if it was a badly intentioned paper. There are things that today one doesn’t speak about anymore, but that back then were fresh and bloody history. And we at least have not forgotten that the Spanish Civil War started out as a general’s rebellion against the democratic institutions that a people had just given themselves liberally. We have not forgotten that this general sent Moorish troops against the people of his country in the name of Christ, and German-Italian legions invoking the Holy Spain. In the indignation that overcame us in 1931 despite the warning signs, there was the feeling that an injustice had just been committed that had to disappear as quickly as possible if one didn’t want it to remain on Europe’s flank like a sore that was going to fester and grow wider. But the injustice still was to receive its reward that this world always reserves for it. Agencies published the Italian legions’ victorious communiques at the same time as the non-intervention ones. The Spanish Republic, firm in its rightfulness, teetered in its power and at first with rage, then with pain that filled us all started to give birth to anguished amazement that has not left us all these years at the spectacle of an injustice that gradually took on an immense scale of history and that found itself sanctioned both by the defeat of a people and by the cowardice of the world. This world, nevertheless, perseveres in calling legal what has been established, while we continue, in vain, to call legal what has been given consent. Of all the reasons that the Spanish war has continued to haunt us, many undoubtedly have vanished today. The cruelty of that struggle seems to us almost natural after five years of indescribable violence. But you can see what remains: the passion of a people and the spectacle of injustice that was never repaired. The hostilities have been suspended, the darkness of the dictatorship has dissipated, and so we continue to carry Spain in our thoughts. At the other end of the continent, a patch of night yet reminds us of the reasons for this war and of the fact that we were wrong believing it to be finished, just as we were wrong nine years ago not believing that it had started. But vanquished courage and injustice consecrated by history are commonplace in this world. And maybe as far as Spain is concerned, our indignation would be less strong if we had a better conscience. How would it be when we cannot forget that France is not the only one to respond to some of the assassinations that shook what was left of the European conscience. The death of Frederic Garcia Lopez thus seems to us less tolerable than others. We had entered a period where every free man could reasonably expect that he would one day stand facing guns of execution. We are still in that period, and it is natural that a free man justifiably prepares himself or at least takes this likelihood into account when he calculates his chances and his convictions. Lorca’s death was in the order of things, in the dirty order in which we have since lived. And the Granada execution put men on alert that they had entered serious times, meaning times where poets could be shot by those whom their existence contradicted. At least some of us have seen it that way and are preparing ourselves instead of complaining. But we have to believe that we were not yet prepared enough. For we needed to go further yet, do our part of the assassinations, and see Antonio Machade die as he was leaving a democratic concentration camp. Some years later, and Companys was liberated by a French Marechal to be executed at leisure. How will we be able to forget? All of this has colored in red and in black a face, that of Spain, that we already carry in ourselves but that we can no longer heal.

********

That is why, since Barcelona was taken, there is an absence in us, an emptiness, a sense of waiting. In this world that we call liberated, there is a country from which we obstinately avert our gaze for it speaks to us of injustice and remorse. We would like peace, but it won’t let us have it. Yet would our heart be as anxious if this subjugated land was not at the same time the land of great passion and grandeur? No doubt I have my personal reasons of choice. Based on blood, Spain is my second home. And in this greedy Europe, in this mechanized world where passion is met with derision, half my blood has been pondering its exile for seven years and wants to find the only land again where I feel at ease, the only land where people know how to unite to a higher degree of necessity the love of living and the desperation of living. But it is not just a personal reaction that rules the hope for a free Spain. All of Europe’s intelligent minds also turn to Spain as if they felt that this sad country held some of the royal secrets that Europe is desperately trying to figure out, right through a long list of wars, revolutions, eras of mechanics and spiritual adventures. In fact, what would prestigious Europe be without poor Spain? What more staggering has it invented than this powerful and magnificent Spanish summer light where extremes are wed, where passion can be indulgent as well as ascetic, where death is a reason to live, where you bring seriousness to dance and lightheartedness to sacrifice, where nobody can tell the border between life and dreams, between comedy and truth. While the Western world tears itself up to discover syntheses and formulas, Spain offers them up freely. But it can only furnish them in the effort of insurrections, the terrible breathing of its liberty. Homeland of revolutionaries (the only country where anarchy has been able to establish itself as a powerful, organized party), its greatest works are calls toward the impossible. In each one, the world is accused, yet at the same time glorified.

*************

Europe and the world, for what they now need to find, can really no longer do without Spain. But Europe and the world do, and in such a natural way that it is hard to believe. But that is the way it is, and nothing apparently is of any use but the testimony of the free man. The indignation will last through the ages, we know that now. For the last twelve years, many Ubu Fathers rose up and we at first laughed about them, but they put irresistible mechanisms in the service of their mediocre follies. And these Ubu Fathers were masters long enough that at their defeat, men were still blind. You have to believe it, at least since we let the latter continue their parade in what was the country of Cervantes. For the past seven years, the grotesque has been the only Spanish product to manifest itself there. And we, who know the value of the grotesque when it has a police, we support that it continue gagging the people of the revolution and that above Spain the windmills of stupidity and cruelty keep turning. And not only do we support the grotesque, but we also sign treatise with them. The democrats are hungry, and honor does noy count for much when you can have some oranges. The lasting smell of those oranges will mingle with the memory of Machade and Companys. Too bad if in the end we have a change of heart.

Why get upset? The realists say that this does not concern us, that you have to leave people to take care of their own business and that finally, we didn’t fight for Spain but against Germany. Democracy, from all it seemed, means not to worry about others. But we learned that democracy means no borders. Misunderstood in one place, it is threatened altogether. And we know better than the realists why we fought. We fought so that free men could look at each other without shame and so that each man would be in charge of his own happiness and would judge himself without carrying the constricting weight of others’ humiliation. That man today can feel himself or actually be free as long as this land of liberty stays entrusted to an arbiter. Every time a man somewhere in the world is weighed down with chains, we are at the same time bound. Freedom must be for all or for no one. That is the only formula of democracy that is worth the sacrifice.

Here at least in the following pages, the testimony of some men who feel they are still not quite free. It is the work of those who have not signed commercial treatise and who will continue to make do without oranges. And there is no doubt their testimony is symbolic. It has to be. But in this world without memory, it is good that some believe in faithfulness. They perhaps will help one day to forgive what, in the rage in their hearts, they could not prevent.

**********

Albert Camus 1945”. This weighty and heartfelt piece was published as Camus’s preface to the book L’Espagne Libre (Paris: Calman-Lévy, 1946), which also included contributions by Jean Cassou, Jean Camp, and others. It has been much quoted over the years, even inspiring the title of a recent book on the Spanish Civil War. One page is yellowed, and there are corrections and cross-outs (one quite large) throughout in Camus’s handwriting. |

| |

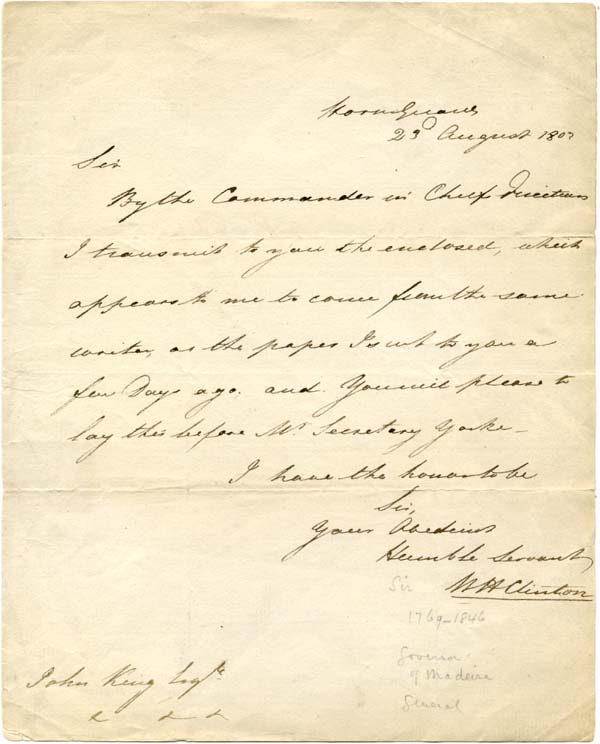

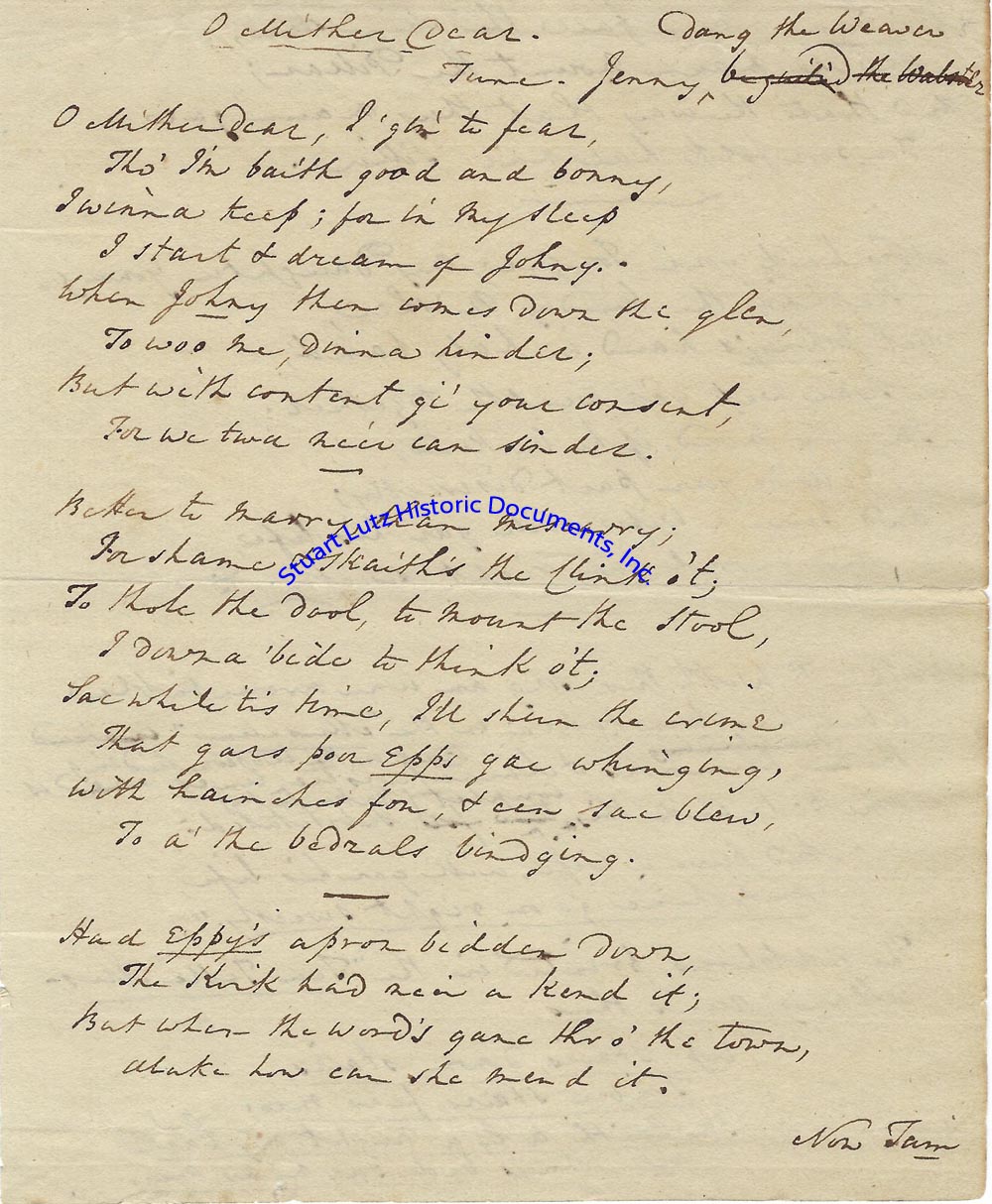

THREE SCOTTISH POEMS, WRITTEN OUT BY ROBERT CROMEK

ROBERT CROMEK (1770-1812). Cromek was an English engraver, art dealer, and editor.

AM. 5pgs. N.d. N.p. A series of three traditional Scottish poems and songs written out by editor and printer Robert Cromek. The poems include “There’s nane o’them a’ like my bonnie Lassie” and “The Lowlands of Holland”. For example: “The Lowlands of Holland My love he built a bonny ship & set her on the sea, With seven score good mariners to bear her company. There's three score of them is sunk & three score dead at sea, And the lowlands of Holland has twined my love & me. My love has built another ship & set her on the main, And nane but twenty mariners all for to bring her hame. But the weary wind began to rise, the sea began to roll, My love then and his bonny ship turn’d widdershins about. There shall neither…on my head nor comb come in my hair, And shall neither coal nor candle light shine in my bower mair. Nor will I love another one until the day I die, For I never lov’d a love but one & he's drown’d in the sea. Oh hold your tongue my daughter dear, be still & be content, There are mair lads in Galloway, you heen nae fair lament. O! there is none in Galloway, there's none at a’ for me, Fer I never lov’d a love but one, & he's drowned in the sea. Note I have heard the two first lines of this verse sung differently an elderly Yorkshire Lady where it seems this Fragment, with a great number of old Scottish ballads, non lost, were popular when she was young. Ed. ‘No boif shall e’er come on my head, nor comb into my hair, No fire light, nor candle bright shall see what beauty’s there.’”. “The Lowlands of Holland” refers to sailors getting pressed into the British Navy against the Dutch. The manuscripts are in very good condition. |

| |

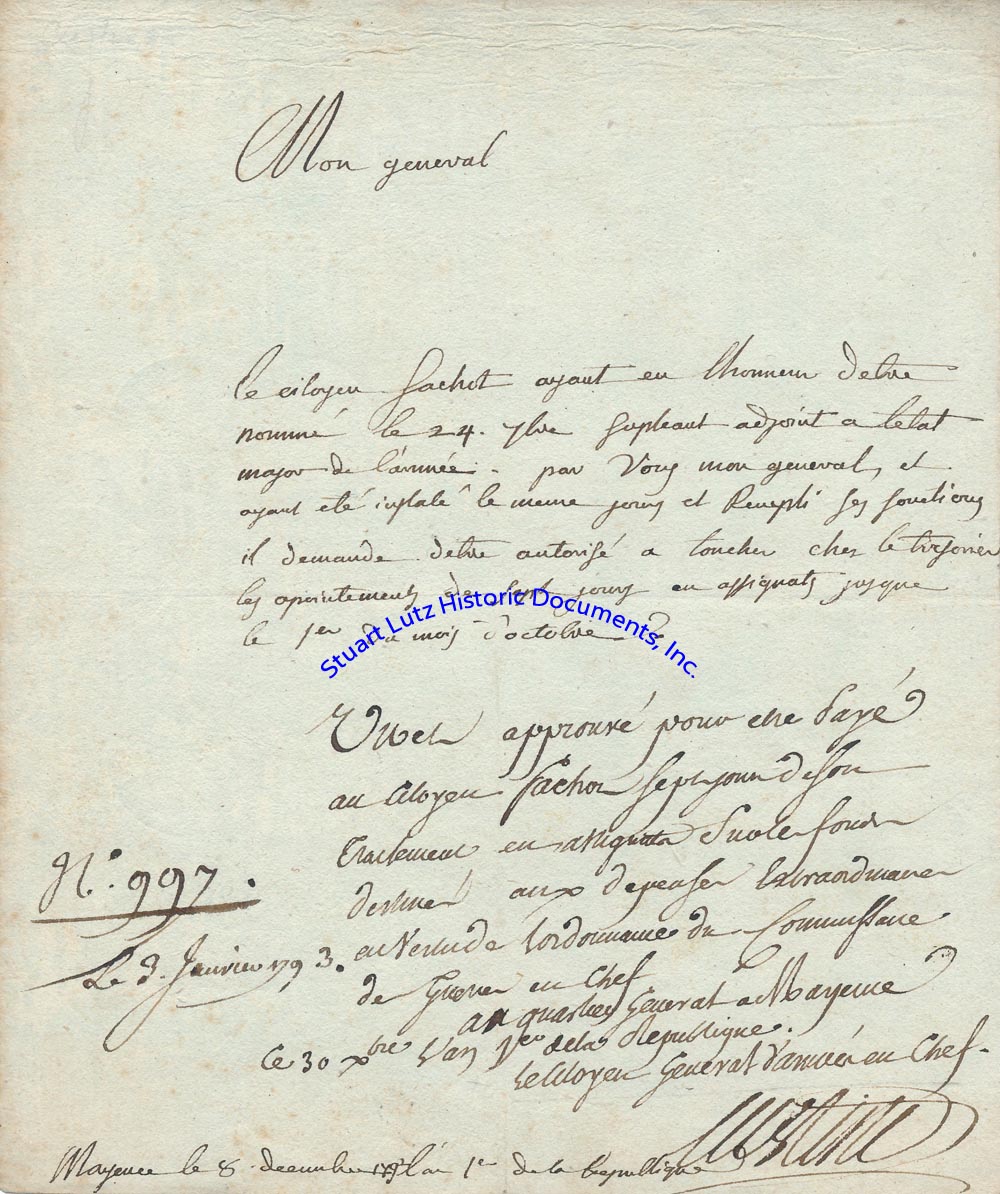

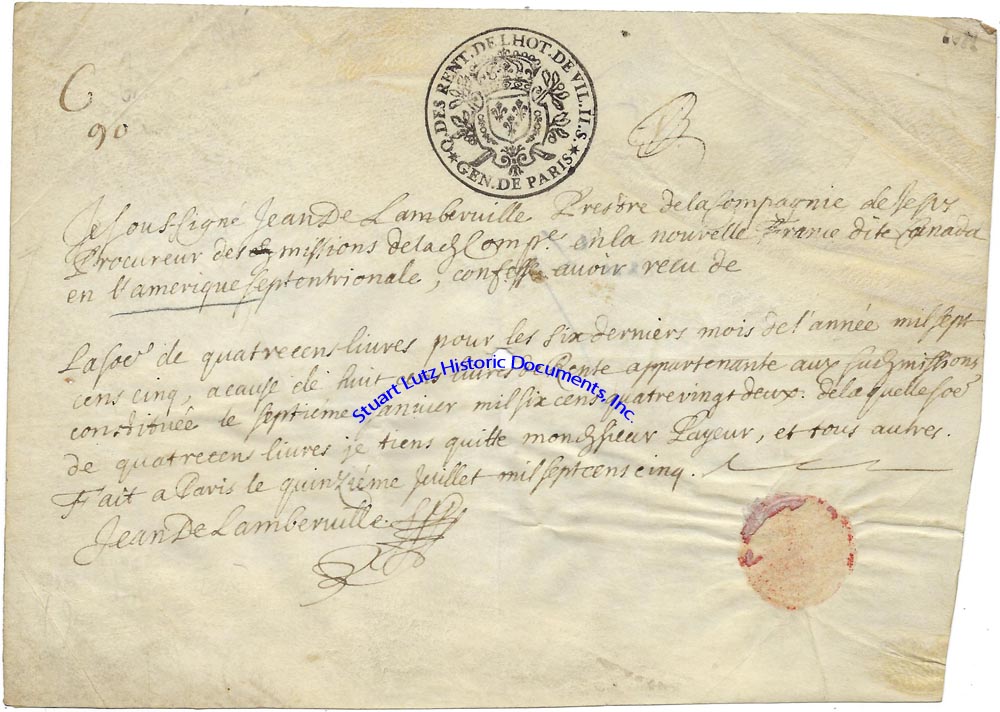

THE RARE AUTOGRAPH OF JEAN DE LAMBERVILLE, THE FRENCH JESUIT MISSIONARY WHO WORKED WITH THE FIVE NATIONS

JEAN DE LAMBERVILLE (1633-1714). Lamberville was a French Jesuit priest who landed in New France in 1669 and was largely stationed in Montreal. He was an important missionary to the Onondagas and converted their chief, and he was a conduit between the Five Nations and the European settlers. He was one of the most influential Frenchman in the New World.

ADS. 1pg. 7 ½” x 5 ½”. July 15, 1705. Paris. An autograph document signed “Jean De Lamberville” twice, once in the text and once at the conclusion. Writing in French, Lamberville penned: “I, the undersigned Jean De Lamberville, priest of the company of Jesus and attorney of the mission of said company in New France, called Canada, in North America, confess to have received of the sum of eighty livres for the last six months of the year 1705 on account of 800 livres rent [government obligation], belonging to said mission and issued on the 7th of January 1682. For the said eighty livres I discharge Mr. Layeur and all others. Done at Paris the fifteenth of July, 1705. Jean De Lamberville SJP”. Father Lamberville likely returned to France around 1700 and remained in France for the rest of his life. The statement is written on vellum and has a red wax seal in the lower right corner that was largely removed. There is a stamp at the top stating that it came from the Department of Rents in Paris, and a small circular hole in the exact center of the document where two folds merged. Generally, autographs of New World missionaries are very difficult to find. According to the RareBookHub, the last Lamberville signed document to sell at auction occurred in 1924, attesting to their rarity. |